Albania is a country located in Southern Europe. With the capital city of Tirana, Albania has a population of 2,877,808 based on a recent census from COUNTRYAAH. After World War II, Albania developed into a fierce communist and atheist dictatorship, where thousands of “class enemies” were executed in Europe’s most isolated country. Dictator Enver Hoxha died in 1985, and a cautious reform policy led to free elections in 1991. Economic collapse was followed by popular revolt, and a UN-sanctioned peacekeeping force was sent into the country to establish the order. A few years into the 2000s, the economy began to grow and a modernization of Albania began.

When the Second World War was over, in December 1945, an election was held in which only the Communists participated. In 1946, the People’s Republic of Albania was formed. In the same year, a friendship agreement was signed with Yugoslavia, and in the spring of 1947, the Yugoslav leader Tito forged plans for a union between Yugoslavia and Albania. The idea was that Albania would merge with Kosovo into the seventh sub-republic of Yugoslavia. These plans came to a quick end when the Moscow regime broke with Yugoslavia in 1948. Albania then became a faithful arms carrier to the Soviet Union, which gained a naval base in the Albanian city of Durrës.

- ABBREVIATIONFINDER: List of most commonly used acronyms containing Albania. Also includes historical, economical and political aspects of the country.

Albanian-Soviet relations deteriorated as the Soviet Union, following the death of leader Josef Stalin in 1953, approached Yugoslavia. In 1961 Albania broke with the Soviet Union and instead made contact with China. The Soviet Union was forced to leave the base in Durres and Soviet assistance was replaced by Chinese. This hampered the economy, which led to demands for change. Hoxha responded with a series of purges in the leadership layers. Check best-medical-schools for more information about Albania.

Terror and isolation

When China established relations with the United States in the 1970s and sought to improve relations with Yugoslavia, Albania also distanced itself from China. In 1978, Chinese aid ceased and Albania’s international isolation became almost total. The constitution of Albania prohibited the government from borrowing money abroad and receiving aid. Nor were foreign companies allowed to establish themselves in Albania.

Hoxha’s regime aroused the disgust of the outside world, which further contributed to Albania’s isolation. No Eastern European country went as far as Albania in imitating Stalin’s methods of coercion and terror. Thousands of “class enemies” were executed, imprisoned, banished in the country or interned in labor camps. At the same time, the Albanian leader became the subject of a fanatical cult of personality.

Enver Hoxha died in 1985. He was succeeded by Ramiz Alia, who initiated a cautious reform policy. But Albania remained the poorest country in Europe and Albanians’ dissatisfaction with the regime increased. In the end, the upheavals in Eastern Europe in 1989 also spread to Albania. More and more people were trying to leave the country, while the demands for democracy were increasing. In December 1990, the regime gave in and allowed multi-party systems.

The Communists win the first election

In March 1991, the first election was held. The Communists got two-thirds of the vote, while the newly formed Albanian Democratic Party (PD) received most of the remainder. The newly elected Parliament recognized the right to, among other things, private ownership, freedom of expression and emigration. A new presidential post was established and Ramiz Alia was appointed president. But the unrest continued. A first government was forced to resign after a few weeks, and in June a coalition government took office in which both major parties were included. The Communists changed their name to the Albanian Socialist Party (PS).

At the same time, the Albanian economy collapsed. The lack of food led to looting and hunger cravings. The mass exodus accelerated. The government was forced to resign and new elections were announced in March 1992. Now the opposition won. PD formed government together with two small parties. President Alia was succeeded by PD leader Sali Berisha.

The Berisha government launched a campaign to wipe out communism. The old Communist Party assets were confiscated and lawsuits were initiated against several former Communist leaders. Socialist Party leader Fatos Nano was sentenced in 1994 to 12 years in prison for abusing international relief. The Socialist Party claimed that Nano was imprisoned for political reasons.

Hunting for old communists

Prior to the 1996 elections, the PD government’s political opponents were harassed. Laws were introduced to exclude executives from the Communist era from public records. Many of the Socialist Party politicians were affected, while the government’s sympathizers were protected. Nevertheless, Sali Berisha himself was a member of the Communist Party during the Hoxha era.

In May 1996, PD won an election boycotted by the Socialists and most other parties. They protested against cheating and were supported by foreign observers. A new PD-led coalition government was formed.

Berisha began to control increasingly simply and gain control over the media. Independent newspapers and the political opposition were constantly harassed by the security police.

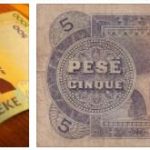

In the New Year 1997, serious popular protests erupted when so-called pyramid schemes collapsed. The Pyramid Games were a kind of investment fund that worked much like a chain letter. Each and every other Alban – ignorant of how a capitalist economy works – had been tempted to invest everything they owned in these funds, which could initially pay out big profits to those who invested money. Eventually, however, the money was not enough and many people became completely exposed when one pyramid after another collapsed.

Popular revolt

The anger of the people now turned to the government, and the political opposition encouraged the protests. By March 1997, the revolt had spread throughout Albania, but worst of all it came to the south. Enraged people broke into weapons stockpiles and soon a large amount of weapons were in circulation. Stores were looted, official buildings set on fire and lawlessness prevailed.

Finally, the government was forced to ask the outside world for help to restore order. In April, 7,000 soldiers from eight countries arrived in Albania. Meanwhile, Berisha had been forced to set up a transitional government and announce new elections.

In the June 1997 elections, the Socialist Party gained its own majority in Parliament. The new Socialist Party Secretary-General Rexhep Meidani was appointed new President. The party’s chairman Fatos Nano, who had been released during the revolt, formed a coalition government. Most foreign soldiers left the country.

At the same time as the parliamentary elections, a referendum was held on whether to reinstate the monarchy. The official result showed that 67 percent of the voters had said no, but the faithful deputy Leka claimed that the figures were false and that a majority had said yes.

The Kosovo crisis is a turning point

The new government’s primary task was to restore order, collect all weapons in operation, deal with the many gang members and dissolve the rebel councils that ruled in several places in the south. To some extent this succeeded, but far from completely. Large numbers of weapons were still out in the community and the economy was in chaos. The government presented an ambitious reform program and was supported by, among others, the IMF.

During the unrest in the Serbian province of Kosovo in 1998–1999 and NATO military intervention, some 450,000 Kosovo Albanians fled to Albania. A NATO force was stationed in the country to protect humanitarian efforts for the refugees. UN staff and aid organizations also came to Albania. The crisis sounded faster than expected when most refugees returned after NATO ceased bombing.

The Kosovo crisis indirectly became a turning point for developments in Albania. The large presence of foreign personnel meant that the country began to be incorporated into the outside world and both the administration and the economy were pushed in the right direction by the inflow of expertise and money.

The parliamentary elections in June 2001 could be carried out with much less of the violence and cheating that affected previous elections. The Socialist Party secured its own majority and could continue to govern.

Political tensions

The socialists’ government holdings had always been characterized by internal power struggles and the government was reformed several times. Fatos Nano, who formed the first government after the 1997 elections, had to resign after just over a year. He was replaced as prime minister by Pandeli Majko, who after one year was allowed to leave Ilir Meta. This one formed a new government after the 2001 election, but had to leave only six months later. Majko then returned as prime minister. After another six months he was allowed to go; Fatos Nano returned as head of government in July 2002.

Nano had been forced to give up trying to become president when Rexhep Meidani’s replacement was elected in June of that year. Instead, the two major parties had agreed on a compromise candidate: former General Alfred Moisiu.

Despite the great internal turbulence during the Socialist Party’s reign, the democratic structures in the country were strengthened gradually. More parties were formed, new media were founded and both individual organizations and business operations grew. But the contradictions were still great between the two dominant political camps.

In February 2004, Berisha and PD called for government-critical protests in Tirana. Police were deployed to prevent thousands of protesters from storming government buildings. Later that month, 50,000 people demonstrated in Tirana demanding Nano’s departure.

Cooperation agreement with the EU

Ever since the fall of communism, a rapprochement with the EU had been an overall goal for both PS and PD. Ahead of the 2005 parliamentary elections, the European Commission had made clear that free and fair elections were a prerequisite for opening negotiations on Albanian EU membership. However, observers pointed to inadequate identification of voters and criticized the two major parties for claiming victory even before the polling stations had closed.

In the election, the PD secured allies in the parliament with allied parties, but the formation of the government dragged on at the time. Only in September was PD able to form a coalition government with six smaller parties. Sali Berisha became new prime minister. Socialist leader Fatos Nano resigned after the election and was succeeded as party leader by Tirana Mayor Edi Rama.

Eventually, the EU noted that Albania had made some progress in a democratic direction. The reward was a Stabilization and Association Agreement with the EU in 2006. Such an agreement is regarded as the first step towards a membership of the Union. In April 2008, Albania was offered membership in NATO and a year later, the country entered the defense alliance.

In the 2009 election, the ruling PD won in an alliance of 17 parties, with barely a margin over a five-party alliance dominated by the Socialist Party. The Socialist Movement for Integration (LSI), an outbreak of the Socialist Party, also took place in Parliament.

Boycotts and violent protests

But the opposition accused PD of electoral fraud and refused to accept the result. For many months, the left boycotted Parliament, with the result that laws needed for the EU’s rapprochement could not be adopted. Sali Berisha, who, after extended negotiations, was able to form a government with LSI, refused to meet the opposition’s demand that the votes be recalculated. Foreign observers felt that the election was better conducted than in the past, although there was pressure on voters.

In the spring of 2010, the opposition boycott was canceled after mediation by the EU, but the conflict escalated. A major protest in Tirana in January 2011 degenerated into violence and harsh police intervention, leading to four protesters being shot dead and many injured.

Local elections in May were accompanied by new violent protests from the opposition, especially in Tirana where Edi Rama was first declared re-elected mayor and then lost to PD’s candidate by a marginal margin. Rama appealed to the Supreme Court before accepting the election loss. In June, the Socialists launched a new boycott of Parliament and returned only after three months. The boycott crippled the legislative work.

Long road to EU membership

Following pressure from the Council of Europe and the OSCE, among other parties, the parties agreed in 2012 to reform the electoral law. Not least, it involved the formation of a more independent election commission. The Council of Europe and the OSCE also stressed that the parties must accept the rules of democracy.

The political power struggle continued to extend Albania’s long road to EU membership. In 2012, the EU found that the country fulfilled only one of the basic requirements for becoming a candidate country: the establishment of a Justice Ombudsman.

In September of that year, the Albanian Parliament voted unanimously to severely limit the judicial immunity of MEPs, senior judges and senior officials. Thus, one of the requirements set by the European Commission was met. Shortly thereafter, the EU Commission recommended that Albania be granted candidate status, provided that a number of other judicial and human rights reforms were completed.